Read this article in Spanish

Featured image: A glade inside the forest canopy of Chapultepec Park, Mexico City, Mexico.

– – –

One of the largest cities in the Americas, Mexico City and its federal district has a population of over 9 million people [1]. From a distance to be a sprawling metropolis absent of wildlife, a testament to humanity’s apocalyptic rule. In reality, the streets of this ancient city are adorned with life. The continuity of this work challenges the concept that humans are completely antagonistic towards nature.

Mar 2020.

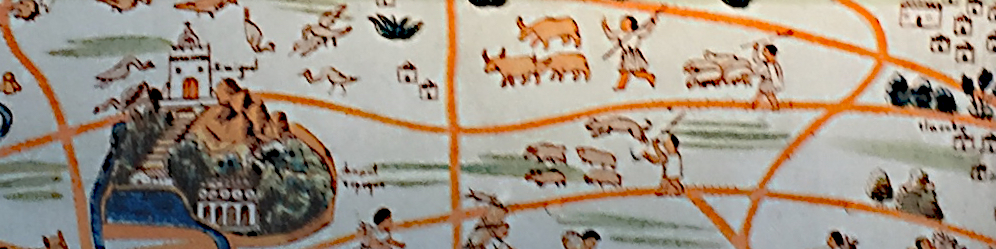

Around the year 1325, prior to its conquest by the Spanish empire, Mexico City was an awe inspiring island city, Tenochtitlan, built around a shallow lake, Lake Texcoco [4]. Tenochtitlan was ruled by a foreign people group called the Mexica [5]. They are most commonly known as the Aztecs, a name derived from the stories they told Europeans of their mythologized ancestral land, Aztlan. The latinization of the Nahuatl language resulted in various pronunciations and stylizations including Mejica, Mejico, and Mexico. The medieval Spanish custom of spelling words using X instead of J persisted in the Americas. México became the name of the entire valley.

Tenochtitlan was a center of commerce and one of the fiercest city states, enslaving and sacrificing people from neighboring regions. Mirroring the reform of religious rituals depicted in the Bible, foreign enlightened rulers like Nezahualcoyotl migrated from nearby city-states and created temples free from human sacrifice. Evidence shows that these people, among other similar groups, had far reaching influence into the southwestern regions of north America. Anecdotes from modern Mexican scholars suggest their couriers reached as far north as Alaska. [2] Their reign came to an end after the arrival of the Spanish.

Left: Chapultepec gardens.

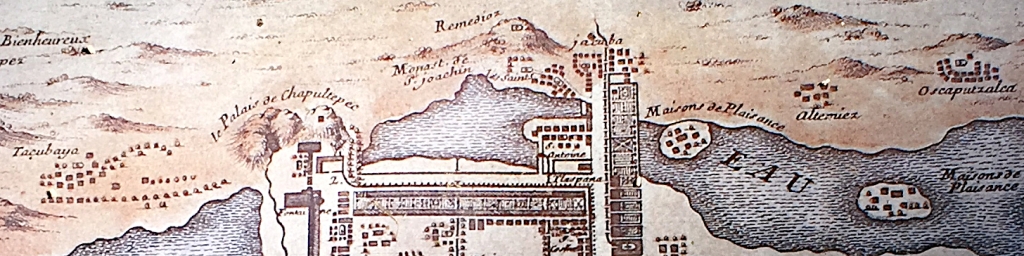

The factors contributing to the success of the Spanish in conquering the region shortly after their arrival in the Caribbean is often overlooked. Relatively few men, the Spanish were fortunate to become allies with Mexica’s coastal enemies and ransacked the city. After establishing control with the superior weapons they had inherited and developed in the Iberian peninsula, they ordered their new subjects to dismantle their largest pyramid and employed artisans to oversee the construction of a new governmental palace using the 1000 year old pumice stone. This process began the dismantling of the Mexica society and its forced assimilation to Spanish custom. For the city of Tenochtitlan, it meant large infrastructural changes that would plague and humiliate the Spanish.

Left: Chapultepec gardens.

The intermingling of European and American culture brought about a revolution in philosophy, culture, religion, and technology. It resulted in the introduction of tomatoes, chocolate, corn, and influx of riches that altered European diet and society, then later the world. Spanish rule put an end to the use of human sacrifice as a state-sanctioned activity. The enduring loss of life, the racial caste system employed by the Castilians, and the relentless indoctrination of scribes and destruction of indigenous literature by the Roman Catholic Church marked a new dark era for the region, which contributes today to many misperceptions.

After experiencing defeat, what is now known as Mexico, became the Spanish colonial territory of the Viceroyalty or Kingdom of New Spain (Virreinato de Nueva España). After continued conquests, New Spain spanned northwards towards the southwestern region of the northern American continent (today’s California, Arizona, New Mexico). Mexico City as one of its largest cities, contending with Puebla for hosting the centralized government. The term Mexico would persist in the Spanish-conquered city, influencing the naming of northern state of New Mexico within the Spanish-controlled territory of New Spain, and finally becoming the official name of the young republic known internationally as the Republic of México, or officially in their own land, the Mexican United States (Estados Unidos Mexicanos).

Mexico City,

Federal District, Mexico, Mar 2020

Chapultepec Castle, Mexico City, DF, MX, Aug 2019

This fascinating city with a tumultuous history is home to many specimens of flowering trees. During the springtime their color brings wildlife to the massive sprawl of human habitation. Butterflies are seen fluttering around the gardens and shaded streets of the city. Birds hop from tree to tree, bush to bush, and their songs can be heard within the constant hum and drone of city life and vehicle traffic. The city’s central park, Chapultepec Park (Parque de Chapultepec) existed during the reign of the Mexica as a royal garden. The prominent hill in Chapultepec became the site for a castle that was later inhabited by a Hapsburg king and would be landscaped by the Belgian and French gardeners [4].

Mexico City, MX, Mar 2020

Mexico City, MX, Mar 2020

The Jacarandá tree, Jacaranda mimosifolia, is the most flamboyant flowering tree of springtime in Mexico City. It adorns many avenues and small city streets. Its flowers fall shortly after its bloom and decorate the dusty side walks and provide work to the city’s maintenance crews. Although it adorns much of the city, it is not native to the area, but instead originates from interior southern American regions and historic territories of the Spanish empire that are now Bolivia, Argentina and Uruguay. The Jacarandá tree has almost worldwide distribution and has been adopted by many countries as an ornamental tree. Its abundance in Mexico City is said to be a result of the work of Tatsugoro Matsumoto, a Japanese immigrant to the Americas, paralleling the introduction of cherry blossom trees to Washington D.C. in the United States of America.

Chapultepec Park, Mexico City, MX, Mar 2020

Chapultepec Park, Mexico City, MX, Mar 2020.

Another tree native to the southern American region near Argentina and frequently seen around Chapultepec and other parks within Mexico City is the Ombú tree, Phytolacca dioica. One of the most fascinating aspects of this tree is its large bulbous root collar. The Ombú’s hanging infloresences provide for simple identification.

Mexico City, MX, Mar 2020.

If you travel enough around the streets of Mexico City, you will find the Mesquite tree, Prosopis spp. , which as a genus has a wide distribution in the Americas and is a landscaping tree in semi-arid regions around the world. Yet, these round yellow inflorescences appear unique to the photographed species.

from Chapultepec Castle, Mexico City, MX, Aug 2019

entrance to Chapultepec Park, Mexico City, MX, Mar 2020.

There are also introduced trees from foreign regions of northern America such as the Southern Magnolia tree, Magnolia grandiflora, which is native to the south-eastern region of the United States of America. The photographed specimen is located behind the large ‘Monumento a Los Niños Heroes’, which was constructed to commemorate a group of heroic young Mexican cadets’ defense of the Chapultepec encampment during the Mexican-American war. Other specimens of M. grandiflora are located around Chapultepec park and are memorials of their own to the intertwining and multi-cultural phenomenon of conflict.

near the Experimental Ceramics Workshop (Taller Experimental de Cerámica),

Mexico City, MX, Mar 2020

A native flowering tree, the Colorín tree, Erythrina coralloides, can be found bare without leaves yet vibrantly red in the Mexico City springtime. The tree is known in English as the Naked Coral tree, and is often found in the south-western United States of America where its native range extends. The term ‘colorín’ refers to its red color, and is also a term used to describe auburn/red-haired people in Spanish. The tree is scattered across the city and parks, and is always a delight to find.

Chapultepec Park, Mexico City, MX, Mar 2020.

The ahuehuetl tree, Taxodium mucronatum, is a native tree with a grandiose history in the region [5]. During the establishment of the island city state of Tenochtitlan, it is said that the indigenous people planted the ahuehuetl tree to anchor clods of earth called ‘chinampas’ to the shallow Lake Texcoco’s floor. Navigating extensive networks of water between mounds, the Mexica people would travel by boat and create the gardens which fed the elaborate city. These trees are related to and resemble the Bald Cypress trees, Taxodium spp., found in the swampy regions of the southern United States of America. The ahuehuetl tree is protected by the Mexican government, and is found abundantly across the Mexico City’s landscape. Due to their protection, some specimens are many hundreds of years old.

Mexico City, MX, Mar 2020

Another popular tree worldwide, the Liquidámbar tree , Liquidambar spp.,has a species from the US, and few species from China. Chances are the specimens in Mexico City are from China. However, the climate of Mexico City closely resembles the climate of the southern tip of eastern Ireland, which could support plants from highlands in the southern US. The pointed round fruit, which looks like a medieval mace, appear similar to the fruit of Platanus spp. trees.

Chapultepec Botany Garden,

Mexico City, MX, Mar 2020

The trees of Mexico City, as well as the countless plants share that the space in the understory, provide an environment for many creatures to thrive such as lizards, birds, and insects such as butterflies. Native swallowtail butterflies, Papilio spp., have an ancient connection to the area of Mexico City and are occasionally seen in the springtime. Mexican grackles or Zanates, Quiscalus mexicanus, are commonly seen in Parque de Chapultepec. Their songs are quixotic and add to the surreal experience.

Mexico City, MX, Mar 2020

Chapultepec Park entrance,

Mexico City, MX, Mar 2020

Chapultepec Park,

Mexico City, MX, Mar 2020

Life in any city is no paradise, and decisions must be made to manage the delicate balance between the needs of wildlife and the needs of the populace. Perhaps rarer than the sight of a yearly Jacarandá blossom is the sight of humans working to prevent them from falling on passing cars and possibly producing fatal or injurious car accidents on the main avenues. Such an activity is rare due to the time it takes for a tree to grow itself into such a predicament. Plants in the gardens are tagged and inventoried.

near Chapultepec Botany Gardens,

Mexico City, MX, Mar 2020

The ancient Mexico City delicately balances its wildlife and urban metropolis. Time will reveal if this balance is sustainable. This is up to the mercy of our changing environment and the actions of city administrators, much like all cities in the Americas. While the world fears the real consequences of human population growth and the destruction of the environment, nature still finds a way to thrive even in the densest, largest, and oldest of human habitats in the continent. Perhaps, the next time you see an image like the one below, you will think twice about its meaning.

The Pines (Los Pinos),

southwest of Chapultepec Park,

Mexico City, MX, Mar 2020

Chapultepec Park,

Mexico City, MX, Mar 2020

Chapultepec Park,

Mexico City, MX, Mar 2020

Mexico City, MX, Jun 2011,

SEDACMaps, Wikimedia Commons [6].

Added white line ≈ 40km = 24.9mi

TUBS, Wikimedia Commons [7]

May 23, 2011,

NASA Goddard Space Flight Center,

Wikimedia Commons [8]

Author: Gustavo Meneses

Published: 2023-01-14

Revised: 2024-03-26

Read more

La Fauna de la Ciudad de México

https://faunacdmx.wordpress.com

Mariposa Cometa Xochiquetzal, Papilio multicaudata

https://www.inaturalist.org/photos/14999931

References

[1] Población total. Censos y Conteos de Población y Vivienda. 2020. Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática (INEGI). Mar 27, 2020. https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/ccpv/2020/

[2] Nava, Jorge. 2019. Tour of National Palace in Mexico City. Personal communication. Aug 2019.

[3] Galindo, Sergio Hernández. 2016. Tatsugoro Matsumoto and the Magic of Jacaranda Trees in Mexico. McNaughton, Kora, translator. Discover Nikkei, May 6, 2016. http://www.discovernikkei.org/en/journal/2016/5/6/tatsugoro-matsumoto/

[4] Park Signage. Fauna & Flora. Plaques near spring baths, Chapultepec, Mexico City, MX. Mar 20, 2020. https://imgur.com/a/1xlefIg

[5] Park Signage. Botanical Garden of Chapultepec. Chapultepec, Mexico City, MX. Mar 17, 2020. https://imgur.com/a/e1jGJsh

[6] File:Mexico City, Mexico (5461525692).jpg, SEDACMaps, Wikimedia Commons, Jun 1, 2011. Accessed Jan 19, 2023. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mexico_City,Mexico(5461525692).jpg

[7] File:Mexico (city) in Mexico (special marker).svg, TUBS, Wikimedia Commons, Aug 4, 2011. Accessed Jan 19, 2023. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mexico_(city)in_Mexico(special_marker).svg

[8] File:Fires and Smoke in Mexico (5752410980).jpg, NASA Goddard Flight Center, Wikimedia Commons, May 23, 2011. Accessed Jan 19, 2023. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fires_and_Smoke_in_Mexico_(5752410980).jpg