Read this article in Spanish

Featured image: Bank of a river with two types of plants.

– – –

Similar to how books titles are italicized, but art and poems are ‘placed within apostrophes’, plant names also have their own formatting conventions.

You may notice italicized complex names such as Quercus rubra, Asimina triloba, or Prosopis spp. By learning about taxonomy, the science of classifying organisms, we can understand what these names truly mean. Nomenclature is the set of official terms or names used in a discpline [1], such as horticulture.

Wikimedia Commons [1a].

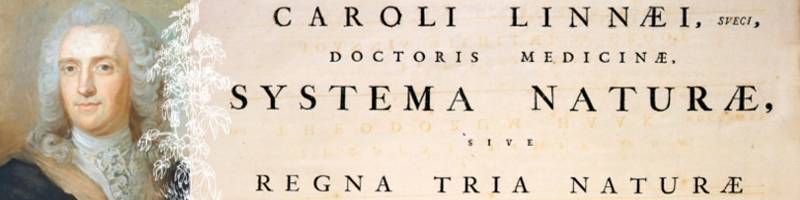

As scientists across Europe began to describe animals and plants, they needed a way to classify them, to better understand their nature, and to communicate this information to a multicultural audience. Old manuscripts were written in Greek and later Latin. These languages created bridges of communication and knowledge amongst the different ethnolinguistic groups. Many names, like Quercus or Oak, can trace back to antiquity.

2. Scarlet Oak, Quercus coccinea

UW-Arboretum’s Longenecker Horticultural Garden (LHG). 2020s.

UW-Arboretum’s LHG. 2020s.

For horticulturalists, systems of classification are useful when they help create a functional order in a world of complexity. Taxonomy seeks to divide all living organisms into a distinct groups or taxa that are ranked by increasing specificity: Domain > Kingdom > Class > Order > Family > Genus > Species. There are intermediate ranks that are less frequently used, as well as minute distinctions that are not included in the ranking system. These rankings correspond with consistent patterns found in a plants at macroscopic and microscopic levels. In plants, the rank of Family correlates with floral characteristics that were observed to be shared among many different species of plants.

Wikimedia Commons [2a].

A species is the most basic description of an organism that remains true for each generation after reproduction. Prior to the binomial naming system, each animal and plant was described in long sentences. The Swedish botanist Carl von Linné, who went by the latin name of Carolus Linnaeus, popularized a method of condensing these long descriptive sentences into a two-word name. Linneaus is considered by many the godfather of nomenclature in the life sciences. Many of the organisms that he described are still named so. When we refer to binomial names, we refer to them as ‘scientific names’, since they are considered to be universal.

Let’s dissect the scientific name Quercus rubra. Quercus means oak in Latin. Quercus is the genus (pl. genera) to which all oak species belong to. Genus, a word of Greek origin, can be translated as a ‘type’, ‘group’ or ‘race’ depending on the context. In the life sciences, genus refers to a higher tiered group that consists of multiple species that may or may not be able to reproduce but share a common ancestor. Depending on our relationship to an organism, we may or may not have common name for a genus. In the case of oaks, all members of the genus Quercus are a type of oak, but this is not the case with all common or folk names for plants. When genera are written by themselves, they are not italicized.

In the scientific name, Quercus rubra, the specific epithet ‘rubra‘ describes which type of oak it is. Together, the genus plus the specific epithet give us the species name: Quercus rubra. A direct translation of its scientific name is the red oak, but that’s not what most people call it. The common name for this plant by English speakers in its native range is the Northern Red Oak. The epithet ‘rubra‘ alone is not part of the ranking system. Specific epithets are descriptors and can refer to the unique characteristics of a species such its color, leaf shape, fruit shape, taste, and physical effects. Many epithets are names of botanists and explorers. Convention requires that the species name is italicized and then abbreviated after its initial use. When handwriting the scientific name is underlined. After mentioning the full species name, Quercus rubra, the genus can be abbreviated: Q. rubra. Specific epithets are often gendered and have traditionally been feminine although there are many exceptions to this rule.

The common name Northern Red Oak might be useful, but it can get complicated since there are many plants given the same name by different people. This creates false similarities between similar sounding names. An example is the word ‘moss’, which is colloquially used refer to plants that are superficially similar but are different at the most fundamental levels of plant biology: true Moss or Bryophytes , Clubmoss (Lycophyte), Spanish moss (Tracheophyte) and Irish moss (Rodophyta).

To refer to multiple species of a genus, instead of a specific epithet, you can use an abbreviation of ‘species pluralis‘ to denote its specificity. If you would like to refer to multiple species of oaks, you could write Quercus spp. , but if you want to ambiguously refer to one species within all the oaks you would write Quercus sp. The ‘spp.’ and ‘sp.’ are not italicized, while the genus name is.

Quercus is an example of a genus that incorporates intermediate rankings, ‘Sections’. Sections can fit within any other division. For oaks, sections are often made to divide the genus into sub-genera, which help differentiate the non-hybridizing groups of Red Oaks from White Oaks.

Wikimedia Commons [3a].

There are more detailed classifications than species. A variety, according to botanical taxonomy, is a sub-rank of species. Varieties are found in nature, separated by some natural barrier. They can be distinct enough to have unique flavor characteristics, nutrient profiles, colors and shape. The name of a variety is shown in the scientific name after the abbreviation ‘var.’ For example, the Thornless Honey Locust is known as Gleditsia triacanthos var. inermis.

There is a separate term for varieties created through breeding. Classifying bred plants is governed by the International Code of Nomenclature for Cultivated Plants (ICNCP). Cultivar, is a commonly used term. The term cultivar is thought by some to be the fusion of the term ‘cultivated variety’. A cultivar is different from any variety of a species, because a cultivar needs to be propagated by humans so that it preserves its unique characteristics. These characteristics might not continue without the involvement of humans. Propagation methods include grafting and replanting propagules.

One regulation determined by the ICNCP is that cultivar names should not be also be translated from their original language if they were written in a Latin script.

There are also levels above and below the cultivar, or altogether different, such as the orchid specific classification, grex.

Wikimedia Commons [4a].

Apple trees are an example of a cultivated plant. If planted by seed, apple trees do not necessarily produce fruit with the same flavor, shape or color as the original apple. Cloning of apple trees can be achieved by grafting. A cutting of the stem with at least 1 bud from the original desired plant, called a scion, is inserted within another stem with roots, called the rootstock. Asexual reproduction makes sure the unique characteristics of the parental variety continue without the genetic variability of sexual reproduction.

The horticulture industry complicates the classification of cultivars by introducing trademark names. These names are used to sell specific plants to homeowners, farmers, and landscape companies. Trademark names are restricted in use, but cultivar names are not. Although it is against regulation, many nurseries create unpronounceable alpha-numerical cultivar names, but then provide a more appropriate sounding trademark name. This practice limits competition by creating the artificial inconvenience of a weird cultivar name.

UW-Arboretum LHG. 2020.

Cultivar distinctions are written in many formats. Some refer to cultivars with the prefix ‘cv.’ and others, like ICNCP suggests, write it in with no prefix and in a non-italicized format.

Here is an example of a type of Panicle Hydrangea, written in the standard ICNCP method: Hydrangea paniculata Le Vasterival GREAT STAR®

In the United States of America, plants are capable of being patented if they are deemed to be bred in a unique manner. This is a contested issue, since some say that the invention of a machine, which what a patent protects, is absolutely different then the modification of a pre-existing organism. This has also led to disputes about cross breeding and genetic contamination of patented or genetically modified organisms (GMO).

In the case of our Panicle Hydrangea, it is not clear whether GREAT STAR® is the intended trademark name. Here is the publicly available patent for the cultivar Le Vasterival, which includes its basic breeding methods and its history in the Norman garden developed by Greta Sturdza, a renown horticulturalist and Norwegian princess in the Romanian Sturdza family.

UW-Arboretum LHG. 2020.

Compare this to Hydrangea paniculata SMHPMWMH CANDY APPLE®, which features the notorious trend of including an unpronounceable cultivar name. The beginning of the cultivar name references the Spring Meadow Nursery.

It is common that unpronounceable cultivar names have some structure or sense to them, often having a few letters associated with the breeder, the original nursery, or as part of a series. Similarly, many cultivars with pronounceable names will also have words of a theme associated with its bred characteristics such as ‘arctic’ or ‘tundra’ to express bred resistance to colder winters, or colorful food and drink like ‘macaroni and cheese’ or ‘wine’ to communicate to others that its has a particular color.

Wikimedia Commons [5a].

In horticulture, breeding results in many hybrids or crosses with beneficial traits of two or more types of plants. This is known as hybrid vigor. To keep track of hybridization or crossing, an × symbol is used.

To explain this system, a new color-coding system is used to describe the naming-process: first plant name, second plant name, combined name, new name

If a plant is a hybrid between two plants within the same genus but two different species then it is referred to as an interspecific hybrid. An interspecific hybrid is written: Genus specific epithet × G. specific epithet. In some cases the abbreviated genus name is omitted: Genus specific epithet × specific epithet.

If the plant is a hybrid between varieties or subspecies within a species then it is referred to as an infraspecific hybrid. An infraspecific hybrid often features a new specific epithet that is a clever combination of the name of the two subspecies or altogether different. An infraspecific hybrid is written: Genus × cleverly combined specific epithet.

If a plant is a cross between two genera then it is referred to as an intergeneric hybrid or cross. An intergeneric hybrid is written: × Genus specific epithet or × Cleverly combined genera specific epithet.

Note: A lowercase ‘x’ is often used instead of the proper symbol ‘×’.

Wikimedia Commons [6a].

In all, taxonomy and nomenclature can be complicated, redundant, confusing, and frustrating. Only after being thoroughly studied can the exceptions and intricacies within ranks, sub-ranks, and the myriad of other conventions begin to be revealed. Many people do not adhere to its principles and others disobey the authorities on the matter. Regardless of the situation, having knowledge about what it all means is imperative to understand horticulture, the urban environment, the craft of landscaping, and modern life sciences.

Author: Gustavo Meneses

Published: 2020-07-29

Revised: 2024-03-26

References

[1] – “NOMENCLATURE”, The Law Dictionary. Accessed Dec 22, 2022. https://thelawdictionary.org/nomenclature/

Images

Featured Image: Natubico. “File:Wild flowers on ditch side (2).JPG”. Wikimedia Commons. Accessed Mar 13, 2024. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Wild_flowers_on_ditch_side_(2).JPG

[1a] of Derby, Joseph Wright. “File:Joseph Wright of Derby The Alchemist.jpg”. 1771. Wikimedia Commons. Accessed Mar 13, 2024. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Joseph_Wright_of_Derby_The_Alchemist.jpg

[2a] Lundberg, Gustaf. “File: Linnaeus av Gustaf Lundberg 1753.jpg”. 1753. Wikimedia Commons. Accessed Mar 13, 2024. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Linnaeus_av_Gustaf_Lundberg_1753.jpg

[…] Linnaeus, Carolus. “File:Systema naturae.jpg”. 1735. Wikimedia Commons. Accessed Mar 13, 2024. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Systema_naturae.jpg

[3a] Hogarth, William. “File:Scholars at a Lecture by William Hogarth.jpg”. 1736. Wikimedia Commons. Accessed Mar 13, 2024.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Scholars_at_a_Lecture_by_William_Hogarth.jpg

[4a] Bauer, Scott. “File:Apples.jpg”. USDA. Wikimedia Commons. Accessed Mar 13, 2024. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Apples.jpg

[5a] Opuntia. “File:Platanus x hispanica Picasso.JPG”. Wikimedia Commons. Accessed Mar 13, 2024. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Platanus_x_hispanica_Picasso.JPG

[6a] Phee. “File:Headache-1557872 960 720.jpg”. Jul 28, 2016. Pixabay. Wikimedia Commons. Accessed Mar 13, 2024. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Headache-1557872_960_720.jpg

Read more

Hints for Understanding Scientific Plant Names. USDA. Internet Archive – Wayback Machine. Website. Accessed Jan 19, 2023. https://web.archive.org/web/20170520014431/https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/detail/ct/technical/ecoscience/?cid=nrcs142p2_011071

Scientific Plant Names. USDA APHIS. Website. Accessed Jan 19, 2023. https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/ourfocus/planthealth/import-information/lacey-act/info-completing-la-declaration/lookup-scientific-plant-names

Linneaus, Carolus. “Systema Naturae”. 1748. Archive.org. Accessed Mar 13, 2024. https://archive.org/details/SystemaNaturae/page/n7/mode/2up