Read this article in Spanish.

Featured image: A light-haired squirrel clinging to the furrowed bark of an oak tree.

And since the portions of the great and of the small are equal in amount, for this reason, too, all things will be in everything; nor is it possible for them to be apart, but all things have a portion of everything.

Άναξαγόρας, Fragment 6, Greece, ~330 BC [1][2]

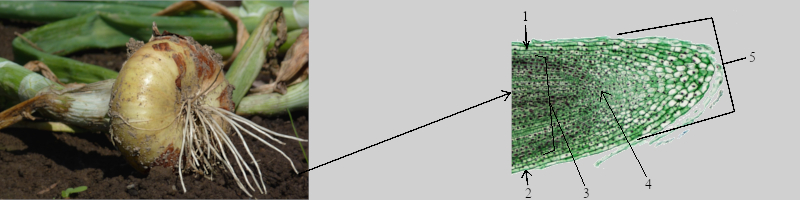

Physics research has developed models to describe several fundamental forces like gravity. Plants respond to gravity by sending signals to each cell as premature seedlings, showing them where gravity is sending them, and telling the rest of its body to grow the other way. This is known as gravitropism. In addition to these responses to universal forces, plants interact with many other entities in the environment.

Abiotic factors

The Sun‘s energy unevenly radiates the surface of the earth. Beyond surface features that block the sun’s rays, factors that contribute to uneven heating include the curvature of earth’s surface and the earth’s axial tilt, which causes the rays of the sun to travel through more atmosphere, causing the energy to diffuse and lessen near the poles [3]. The heat generated at the surface heats the air. Heat emitted from the earth’s surfaces is emitted back down by the clouds. Have you ever seen frost after a cool clear night in late autumn or noticed the temperature get warmer on a cloudy day in winter?

Differences in the properties of air masses in all three directions causes weather. Weather changes influence wind speeds. Winds carry spores to suitable new environments, help spread pollen to pollinate plants far away, and carry seeds far enough to get chance for a seedling to find sunlight. Many plants, particularly grasses, rely on wind pollination.

The average weather conditions over a long period of time creates climate. Climates can take a long time to change. Rocks on the surface that were once molten lava have been through multiple changes in climate worn down into soil.

One of the molecules that affects the conditions in which plants thrive is water. That’s not to say that all plants need lots of water, nor that there are plants that can live with very little water. Water is a constituent in a plant’s vascular system, its “veins”. Not all plants have vascular systems. Those that don’t tend to live near or in water.

Carbon is one of the most important elements for plant life. Carbon dioxide is a gas in our atmosphere, produced in abundance by the combustion of materials in energetic atmospheric events like lightening or making contact with energetic materials like molten lava. Carbon dioxide enters leaves through the pores or stomata (stoma), and diffuses into the liquid of its tissues. Almost all plants are characterized by their ability to use sunlight to catalyze reactions that turn carbon in the air into carbon in a sugar (carbohydrate) that cells can use as energy. Carbon in organic matter provides texture to soils that helps it regulate water, and influence electromagnetic reactions between molecules in the microscopic soup between particles in the soil. One reason why we associate carbon as a bad element is its role in the atmosphere’s ability to retain the Sun’s reflected energy and therefore alter the way energy transfers on the planet’s surface, in particularly with water.

There are also inorganic forms of the essential plant nutrients: Nitrogen, Phosphorus, and Potassium. N. Nitrogen atoms are found in proteins. Inorganic nitrogen is the primary source of nitrogen for plants. Nitrogen in its gaseous diatomic state makes up 70% of our atmosphere. Microbes help plants turn that nitrogen into a form they can consume. Animal waste products contain organic forms of nitrogen that microbes metabolize into inorganic nitrogen through a process known as nitrification. P. Phosphorus atoms are found in phospholipid cell membranes. K. Potassium atoms play a role in the enzymes that are involved in photosynthesis, regulating the movement of water, and regulating the stomata, where gaseous water and oxygen are expelled as waste products and carbon dioxide enters.

Microorganisms

It all began with an oak tree. When scientists developed microscopy, they began to observe the tiniest of patterns in their environment. Scientists observed cork, the exterior bark of Quercus suber, which had been harvested and used commonly. After observing cork, they found that there were these small compartments that created the fabric of this growing living material ripped off the trunks of trees at harvest. These small compartment became known as cells.

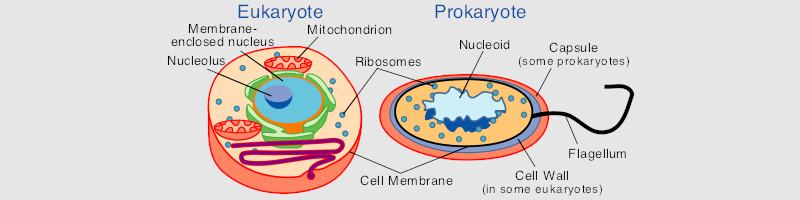

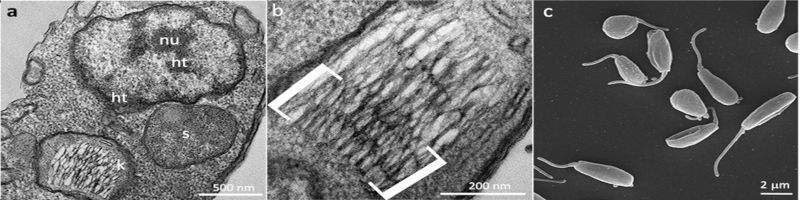

When observing other microscopic life forms, they began to notice that cells weren’t all the same. Some were part of a unit, and others were alone. After identifying all the patterns of cells, we found that all life forms can be divided into two groups: eukaryotes (true nucleus) and prokaryotes (before nucleus). The prokaryotes are unicellular organisms that are much smaller than eukaryote cells on average. Differences between microorganisms resulted in the acknowledgement of the separate prokaryotes, Bacteria and Archaea, and single-celled eukaryotes called Protozoans. Protozoans look similar to prokaryotes, but their organelles (structures inside the cell) function the way animals, plants, and fungi do. Some examples of organelles are the nucleus, mitochondria, and chloroplast. Terrestrial plants, algae, and cyanobacteria have chloroplasts that allow them to create energy using the rays of the Sun.

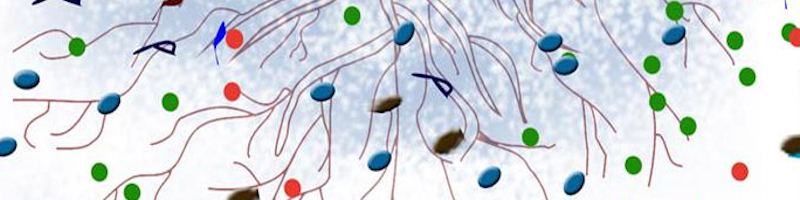

When discussing microorganisms, it makes sense to conceptualize them as living in a biome, just as plants in a boreal forest or a tropical jungle perform different functions. Plant microbiomes are the spaces where other smaller organisms live close enough to influence the plant. They live in soil, near the roots, in the roots, in the tissues like the stem and the leaves, or on the surfaces exposed to the air.

Microorganisms’ activity in the soil can change its chemistry. Microorganisms can be a source of plant nutrients, but can also compete with plants for nutrients. Microorganisms play vital role in soil nutrient cycles.

We might be scared of bacterial infections, or bacteria that function as animal or plant pathogens. Most prokaryotes preform very important positive or neutral functions in plants, even our own bodies. We are still surveying all the different kinds of microorganisms present in plants, and studying what effects they have on plants.

Fungi

Of all the micro- and macro-organisms, fungi are the most similar to plants at the cellular level. Fungi are mostly large networks of veiny structures called hyphae, and can produce fruiting structures. Mushroom caps that we know as fungi are the fruiting bodies responsible for dispensing spores. Fungi and certain plants both reproduce by producing spores. Ferns are an example of a plant that produces spores.

One of the most studied fungi are mycorrhizal fungi that live under the influence of the roots of plants. These fungi react and work together with plants to increase the area of the plant’s roots influence in the soil, provide nutrients, and take sugars. 90% of land plants have interactions with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi.

Some fungi may change the appearance of plants. A class of fungi known as rusts can cause the tissues of plants to swell in order for the fungi to produce a fruiting body that will release spores. Some rusts require two different plants (alternate hosts) in order to complete their cycle. One rust, Apple-cedar rust, causes galls to form on the leaves of apples and hawthorns, and large fruiting bodies on junipers (colloquially called cedars, when a species grows like the tree).

Other rusts with alternate hosts can cause significant problems for humans. Wheat rusts create fruiting bodies on the small kernels, causing significant consequences for their mass processing into flour. Wheat rusts can live on barberry plants. During the 1900’s the government urged farmers not to plant barberry.

Of course, many have experienced the odd pleasure of truffles, or a nice warm dish with portobello mushrooms. Some fungi can be sources of food and medicine, for example Reishi mushrooms, despite not being as nutritious as other foods. Native Americans in Mexico, and some in modern-day Mexico, eat corn that has been infected with fungi. Classified as a corn smut, it is different than a rust because rusts affect leaves, whereas smuts affect the corn itself. It causes the kernels to enlarge, and when too mature to fill with black spores. The infected corn is prized by some due the way it augments the nutritional value of corn, and changes its flavor and texture [6].

Animals

Plants on the land interact with all the organisms that we call animals. The word animal stems from the Greek word ἄνεμος (anemos) and the Latin word animus, which means breathe/soul/wind. Ancient observers saw and classified animals as organisms with some life force that caused them to move. It’s that movement that characterizes the way plant’s interact with them. Are they flying up to the flowers, crawling on the leafs and stems, burrowing into the tissues, digging into the soil, cutting the tissues, or burying the seed for the next season?

Arthropods

Did you know that roly-polies have more in common with lobsters, crabs, and shrimp than with other insects? That’s why when we talk about the creepy-crawly things in life, we broaden the scope to all arthropods, which includes animals with exoskeletons and jointed limbs like spiders, insects, mites, and crustaceans.

Of all these arthropods, insects have some of the most specialized relationship with plants. Of all of the organisms that interact with plants, we should care the most about insects because they have often developed very unique relationships with plants. Some plants have flowers suited only to accept interactions with certain type of insect mouthparts. The chemicals expelled and exuded by plants deter most insects but others might have adapted to it for a special purpose. Monarch butterfly caterpillars ingest high quantities of cardiac-glycosides from milkweed, making them toxic to birds.

Insects, like fungi and bacteria, can alter the composition of tissues in plants. Small wasps can burrow into the flesh of oaks, creating oak galls. The insect within certain oak galls have been the source of the color crimson, the primary ingredients in oak gall ink used by early manuscript writers, and one of the ingredients in the improved iron gall ink recipes.

Fish

Fish and aquatic plants have interdependent relationships [7]. Aquatic plants oxygenate water for fish, provide shelter and food. Fish waste can later provide nutrients to aquatic plants.

Birds

Birds interact with plants in ways that other animals can’t because many birds can fly. The increased mobility of birds is vital to the spread of plants across the environment. Birds are one of the reasons invasive plants tend to move so rapidly across the environment. One plant introduced from Europe to the Americas, buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica) was used to create the hedges and windbreaks that separated farms. A chemical compound found in the fruit causes birds and other mammals to experience diarrhea, therefore increasing the rate at which the seeds are released from the animal’s bowels.

Unique birds like hummingbirds have complimentary relationships with unique plants that have flowers shaped only so that certain hummingbirds can use their long-tongues and small agile bodies to consume its nectar, a hard resource to produce. Birds also use their beaks to open pine cones and crack open fruit. It’s not a coincidence that humans fill bird feeders with seeds from plants!

Some seeds, like those from hot pepper plants, are covered with capsaicin that interacts with the membranes in animals causing the sensation of heat or burning discomfort. Birds, however, don’t experience this sensation since they lack the receptors that react to capsaicin. It is thought that this is an adaptation to protect the seeds from being chewed and destroyed by mammals with teeth. Seeds chewed by animals didn’t survive, and the genetic material inherited to the next generation came from the seeds that weren’t chewed: the ones that were spicy. Birds don’t have teeth, and will swallow seeds whole depending on the species of bird and species of plant, giving them the chance to go through their bowels intact.

Mammals

Many mammals are herbivorous and have adapted to eating specific types of plants. Ruminants, such as cows and horses, have developed special teeth to grind the silica-laced blades of grasses, and specialized stomachs to help digestion. It is thought that the proliferations of grasses on Earth caused mass extinction of herbivorous animals. Camels have the amazing capacity to eat thorny cacti due to a special lining of protective tissues in their mouths, esophagus and stomach. Giraffes have tall necks to help reach all of the tree’s leaves. Primates forage fruit and have hands specialized to open or peel them, as do raccoons, opossums and other rodents to a lesser degree.

An individual mammal can live for many seasons, like birds but unlike many terrestrial arthropods. Mammals will store food for the dormant season, and in the process help plants by dispersing their seeds.

Some fruit today has no known consumer. One example is Osage Orange (Maclura pomifera), which is thought to have been eaten by mastodons or other ice-age mammals[8]. Other seeds like that of the Kentucky Coffee tree (Gymnocladus dioicus) need to undergo breakdown of their seed coats from the stomach acid of animals that no longer exist in the region.

Humans

Let’s consider the previous dilemma of Kentucky Coffee Tree seeds. How do Kentucky Coffee Tree seeds germinate successfully without their associated animals? Humans have, since their presence in the Americas, used seeds like the Kentucky Coffee Tree seeds for games, where they scratch off portions of the seed coat making them quickly viable if thrown into the soil. After the arrival of sea-voyagers and the subsequent massive migrations from Europe in the Americas, humans would use chemical treatments of sulfuric acid to remove the seed coat, in order to control the germination rate and planting of these trees in the landscape.

Humans interact with plants in many ways that other animals do. Humans strategically cut down trees like beavers, forage for berries like bears, open fruits like other primates, drink nectar like birds and insects, farm other animals like ants, store seeds like rodents, we eat leaves and fruits like omnivores and herbivores, and recently have become pollinators like insects.

Although the plant kingdom and its biological history predate the existence of humans, human history is important to understand when studying plants. Humans have the most complicated relationships with plants. The structure of our societies have been largely influenced by the methods of plant cultivation.

Among them are farming and breeding of grasses, and the cultivation of trees for wood. Grains have been cultivated in monoculture to produce massive quantities that would be processed into a powder called flour, which humans use to bake breads that fill the stomach with dietary fiber. Wood from trees each have unique properties and are not just used for furniture, writing paper and houses, but also are used today in airplanes, cardboard and toilet paper, and musical instruments [10].

These two activities have dictated the state of our existence by changing how we manage forests, and soil under cultivation. It is important to know that not all methods of cultivating food and materials are sustainable, and alternatives and opportunities for improvement exist.

One aspect of humans that changes how we interact with plants is our consciousness. Unlike the grasses that caused the extinction of pre-ruminants, we are sufficiently aware of the negative consequences of our collective behavior to be able to communicate them amongst each other. We devise ways to change how we consume what plants have to offer, which includes gardening plants. Many plants will not continue to exist without humans.

Our ability to achieve the herculean task of managing our environment requires that we not only focus on plants but also concern ourselves with the decisions in our lives and our relationships. If we foster human life and take care of each other then it will be easier to be stewards of the land.

Author: Gustavo Meneses

Published: 2023-02-13

Revised: 2024-03-15

References

[1] Burnet, John. “Early Greek Philosophy”, London: A & C Black Ltd., 1920. Demonax: Hellenic Library. Website. Accessed Feb 13, 2023. http://demonax.info/doku.php?id=text:anaxagoras_fragments#the_fragments

[2] Hughes, J. Donald. “Environmental Problems of the Greeks and Romans: Ecology in the Ancient Mediterranean, Second Edition”, John Hopkins University Press, pg.59

[3] “Climate & Biomes”. Biology 1409: Man and The Environment Laboratory, Angelo State University. Spring 2017. Website. Accessed Feb 13, 2023.

https://www.angelo.edu/faculty/mdixon/ManEnvironment/climate2.htm

[4] “What nonpareil corkboard is”, “Nonpareil Corkboard Insulation for Cold Storage Warehouses (…)”. Armstrong Cork Co., Harvard University, 1915, pg.14

https://archive.org/details/nonpareilcorkbo01compgoog/page/n18/mode/2up?q=nonpareil

[5] Feijen, FAA. Vos, RA. Nuytinck, J. Merckx, VSFT. “Evolutionary dynamics of mycorrhizal symbiosis in land plant diversification.” Scientific Reports, vol 8, article no. 10698, 2018. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-018-28920-x

[6] Spraker, Joe.”Huitlacoche.” Division of Extension – Wisconsin Horticulture. UW-Madison. June 7, 2013. Website. Accessed Jan 31, 2023. https://hort.extension.wisc.edu/articles/huitlacoche/

[7] Petr, T. “Interactions between fish and aquatic macrophytes in inland waters. A review.” Food and Agriculture Organization Fisheries Technical Paper. No. 396. Rome, FAO. 2000. https://www.fao.org/3/X7580E/X7580E00.htm#TOC

[8] Pallardy, Richard. “The curious case of the Osage orange and the megafauna extinction”, earth.com, Sep 19 2018.

https://www.earth.com/news/osage-orange-megafauna-extinction/

[9] Janick, Jules. “ANCIENT EGYPTIAN AGRICULTURE AND THE ORIGINS OF HORTICULTURE.” (2002).

https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/ANCIENT-EGYPTIAN-AGRICULTURE-AND-THE-ORIGINS-OF-Janick/b44ce743fd0b6c22923ee2ec9a6de7b1815be5ff

[10] Conners, Terry. “Products Made From Wood” Univ of Kentucky Cooperative Extension Service, FORSFS 02-02, Jul 2002. https://www.dec.ny.gov/docs/lands_forests_pdf/woodproducts.pdf

[11] “Carver’s Bulletins”, USDA National Library Digital Exhibit. Website. Accessed Feb 13, 2023. https://www.nal.usda.gov/exhibits/ipd/carver/exhibits/show/bulletins/carver

Read more

Clayton, Michael W. “Views of Elodea tissue at different planes of focus with DIC illumination showing flagellated bacteria, mitochondria, chloroplasts, and a nucleus with visible nucleolus.” Univ. of Wisconsin-Madison Digital Collection. https://digital.library.wisc.edu/1711.dl/ZGZA3MRJZDFS58H

Lichtenstein, Drew. “Differences Between Protozoa & Protists”. Sciencing. Website. Accessed Oct 11, 2023. https://sciencing.com/differences-between-protozoa-protists-8472038.html

Images

[1a] “File:Figure 2.1 Global average energy budget of Earth’s atmosphere (6080398732).jpg”, US Government Accountability Office, Wikimedia Commons, Aug 25 2011 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Figure_2.1_Global_average_energy_budget_of_Earth’s_atmosphere_(6080398732).jpg

[2a] Kelvinsong, “File:Warm front.svg”, Wikimedia Commons, Dec 31 2014, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Warm_front.svg

[3a] Lavinsky, Robert M. “File:Graphite-and-diamond-with-scale.jpg”, Wikimedia Commons, Apr 4 2015, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Graphite-and-diamond-with-scale.jpg

[4a] “File:Atmosfaerisk spredning.png”, Wikimedia Commons, https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/1c/Atmosfaerisk_spredning.png

[5a] Stewart, Charles L. Land tenure in the United States – with special reference to Illinois. Univ of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, 1915, Archive.org

https://archive.org/details/landtenureinunit0stew/page/n369/mode/2up

[6a] Caudullo, Giovanni. “File:Quercus suber range.svg”, Wikimedia Commons, July 29 2016, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Quercus_suber_range.svg

[7a] Grobe, Hannes. “File:Quercus suber algarve.jpg”, Wikimedia Commons, Oct 15 2005, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Quercus_suber_algarve.jpg

[8a] Niehaus, Carsten. “File:Quercus suber corc.JPG”. Wikimedia Commons, Mar 21 2004, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Quercus_suber_corc.JPG

[9a] “File:The Architect and engineer of California and the Pacific Coast (1910) (14761726926).jpg”, Internet Archive Book Images, from ad in catalogue “The Architect & Engineer of California and the Pacific Coast.” 1910.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Architect_and_engineer_of_California_and_the_Pacific_Coast_(1910)_(14761726926).jpg

https://archive.org/details/architectenginee2210sanf/page/n294/mode/1up

[10a] Tong, Kevin. “NCNC Lab”, UC Davis College of Engineering, May 25 2012.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/ucdaviscoe/7375840012/in/photostream/

[11a] Mortadelo2005, “File:Celltypes.svg”, Wikimedia Commons,

Science Primer (National Center for Biotechnology Information).

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Celltypes.svg

[12a] domdomegg, “File:Differences between simple animal and plant cells (en).svg”, Wikimedia Commons, Jan 18 2019

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Differences_between_simple_animal_and_plant_cells_(en).svg

[13a] Gonçalves, CS. Costa Catta-Preta, CM. Repolês, B. Mottram, JC. De Souza, W. Machado, CR. Motta, CMM. “File:Angomonas deanei.jpg”, Wikimedia Commons, Apr 28 2021,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Angomonas_deanei.jpg

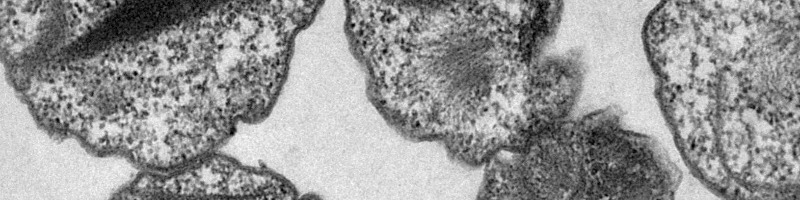

[14a] Mediannikov, O. Sekeyová, Z. Birg, ML. Raoult, D. “File:Diplorickettsia massiliensis Strain 20B bacteria grown in XTC-2 cells Transmission electron microscopy; staining with red ruthenium..jpg”, Wikimedia Commons, Aug 30 2013,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Diplorickettsia_massiliensis_Strain_20B_bacteria_grown_in_XTC-2_cells_Transmission_electron_microscopy;_staining_with_red_ruthenium..jpg

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0011478#pone-0011478-g002

[15a] Maulucioni, “File:Archaea.png”, Wikimedia Commons, Apr 10 2020, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Archaea.png

[16a] Lamiot, “File:Microbiomes végétaux Plant microbiome.jpg”, Wikimedia Commons, Feb 22 2019, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Microbiomes_végétaux_Plant_microbiome.jpg

[17a] Ramjchandran, “File:Fungus 2.jpg”, Wikimedia Commons, June 4 2015,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fungus_2.jpg

[18a] AHiggins12, “File:HYPHAE.png”, Wikimedia Commons, May 31 2021

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:HYPHAE.png

[19a]”File:Apical Meristem in Allium Root Tip (23581053848).jpg”, Berkshire Community College Bioscience Image Library, Wikimedia Commons, Jun 13 2017

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Apical_Meristem_in_Allium_Root_Tip_(23581053848).jpg

[20a] Jamain, “File:Onion J1.jpg”, Wikimedia Commons, Aug 9 2013. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Onion_J1.jpg

[21a] van de Velde, Paul. “File:Spores (Explore) (22367141629).jpg” Wikimedia Commons, Oct 23 2015, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Spores_(Explore)_(22367141629).jpg

[22a] Idéalités, “File:Huitlacoche cuisine.jpg”, Wikimedia Commons, Nov 27 2018.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Huitlacoche_cuisine.jpg

[23a] McMasters, Melissa. “File:Pillbug (28509283724).jpg”, Wikimedia Commons, Aug 19 2016,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pillbug_(28509283724).jpg

[24a] Cbarlow, “File:Pawpaw flowers insect visitors not pollinators.jpg”, Wikimedia Commons, Apr 15 2021.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pawpaw_flowers_insect_visitors_not_pollinators.jpg

[25a] Chelsi, H. “File:Water lilies white flowers nelumbo lutea or american lotus.jpg”, US Fish and Wildlife Service, Wikimedia Commons

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Water_lilies_white_flowers_nelumbo_lutea_or_american_lotus.jpg

[26a] Phil’s 1stPix, “Tilapia Packed Tight at Blue Springs State Park”, Flickr, Jul 9 2021

https://www.flickr.com/photos/1stpix_diecast_dioramas/51437343152/in/photostream/

[27a] Reago, A. McClarren, C. “File:American Wigeon (24032251418).jpg” Wikimedia Commons, Oct 21 2017

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:American_Wigeon_(24032251418).jpg

[28a] Martins, Cesar I. “File:Hummingbird – Beija-flor (14764216168).jpg”, Wikimedia Commons, July 4 2014.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hummingbird_-Beija-flor(14764216168).jpg

[29a] Bargen, Danilo. “File:Guano Island (256096327).jpeg”, Wikimedia Commons, Jul 4 2015.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Guano_Island_(256096327).jpeg

[30a] Shyamal, L. “File:Migrationroutes.svg”, Wikimedia Commons, Feb 2008.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Migrationroutes.svg

[31a] Munns, Edward N. “File:The distribution of important forest trees of the United States (1938) Maclura pomifera (20788162940).jpg”, USDA National Agricultural Library, 1938, Wikimedia Commons, Aug 29 2015

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_distribution_of_important_forest_trees_of_the_United_States_(1938)Maclura_pomifera(20788162940).jpg

[32a] “File:Osage Orange in Arlington National Cemetery (29650566083).jpg”, Arlington National Cemetery, Wikimedia Commons, Oct 11 2016. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Osage_Orange_in_Arlington_National_Cemetery_(29650566083).jpg

[33a] dankeck, “File:Westover Park (30946179121).jpg”, Wikimedia Commons, Oct 27 2016

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Westover_Park_(30946179121).jpg

[34a] St John, James. “File:Burning Tree Mastodon excavation site, Burning Tree Golf Course.jpg”, Wikimedia Commons, Dec 12 2006.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Burning_Tree_Mastodon_excavation_site,_Burning_Tree_Golf_Course.jpg

[35a] LBM1948, “File:Karnak, relieves 1999 09.jpg”, Wikimedia Commons, Apr 1999.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Karnak,_relieves_1999_09.jpg

[36a] Little, Erbert L. “File:Gymnocladus dioicus range map 1.png”, USGS Geoscience and Environmental Change Science Center, Wikimedia Commons, 1977. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gymnocladus_dioicus_range_map_1.png

[37a] Eichmann, Gerd. “File:Baden-Baden-Gymnocladus dioicus-94-Geweihbaum-Frucht-2009-gje.jpg”, Wikimedia Commons, Nov 7 2009.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Baden-Baden-Gymnocladus_dioicus-94-Geweihbaum-Frucht-2009-gje.jpg

[38a] Renz, Jeran. “File:Gymnocladus dioicus seed.svg”, Wikimedia Commons, Apr 29 2022. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gymnocladus_dioicus_seed.svg

[39a] “File:Cucurbita hand pollination page 78 of “Luther Burbank, his methods and discoveries…” (1914).jpg” Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons, Jul 29 2014.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cucurbita_hand_pollination_page_78_of_”Luther_Burbank,his_methods_and_discoveries…”(1914).jpg

[40a] “File:Missouri alley cropping (26245618751).jpg”, National Agroforestry Center, Apr 8 2016.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Missouri_alley_cropping_(26245618751).jpg

[41a] “George Washington Carver Painting”, Tuskegee University Archives, Encyclopedia of Alabama.

http://encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/m-2169

[42a] “File:The Forest products laboratory; (1921) (14584842400).jpg”, Internet Archive Book Images, 1921 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Forest_products_laboratory;(1921)(14584842400).jpg

[43a] “File:Photograph of Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) Enrollee Crew Planting – NARA – 2128744.jpg”, U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Aug 1940

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Photograph_of_Civilian_Conservation_Corps_(CCC)Enrollee_Crew_Planting–NARA-_2128744.jpg

[44a] “File:Trays (7687102420).jpg”, USDA NRCS South Dakota, Jun 28 2007,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Trays_(7687102420).jpg

Extra images

[I] “File:Water transpiration bag.jpg”, United States Armed Forces, Wikimedia Commons, before 1999

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Water_transpiration_bag.jpg

[II] Toews, M. W., “File:Surface water cycle.svg”, Wikimedia Commons, Oct 1 2007

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Surface_water_cycle.svg

[III] tanakawho, “File:Ornithogalum arabicum491228475.jpg”, Wikimedia Commons, May 9 2007.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ornithogalum_arabicum491228475.jpg

[IV] “File:Maculura pomifera (Osage Orange) (31284262414).jpg”, Plant Image Library, Wikimedia Commons, Jan 5 2017.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Maculura_pomifera_(Osage_Orange)_(31284262414).jpg