Read this article in Spanish.

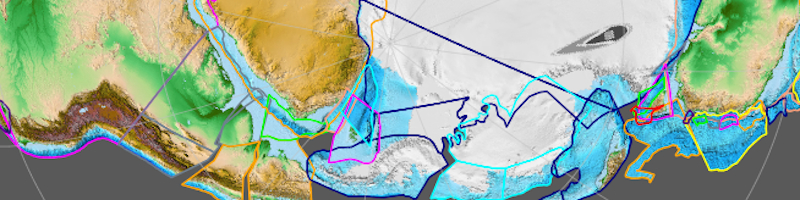

Featured image: A chain of volcanic lakes formed from Andean glacial melt along the Los Lagos region of southern Chile. []

Argentina (bottom left/center), Bolivia (bottom right). Google, 2023.

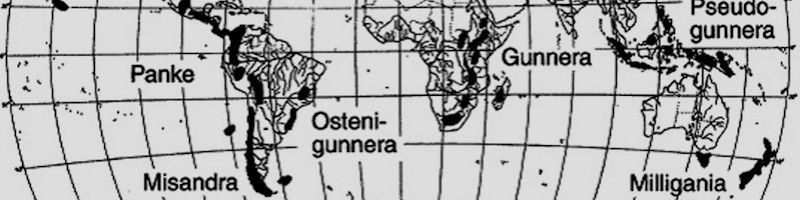

Isolated by the driest desert in the world, the Atacama desert, and the Andes mountains, Chile is a unique land that shares plant species with Pacific islands such as New Caledonia, New Zealand, and Australia. Once a part of the supercontinent Gondwana, species found in Chile are also found in as fossils in Antarctica and living species of grass are found as far as South Africa [1].It is as if you took the west coast of the United States and flipped it upside down.

The unique landform hosts a diversity of indigenous tribes. Perhaps the most prestigious of all historic peoples, the Inca, properly known as the Tawantinsuyu empire [3], stretched from Peru down to the Atacama and at one point included the central valley of Santiago [4] [5]. In the north, the Aymara and other tribes built homes that are preserved in the dryness of the Atacama desert. These desert conditions has preserved many other tribes’ pottery showing how advanced they had become in the arts.

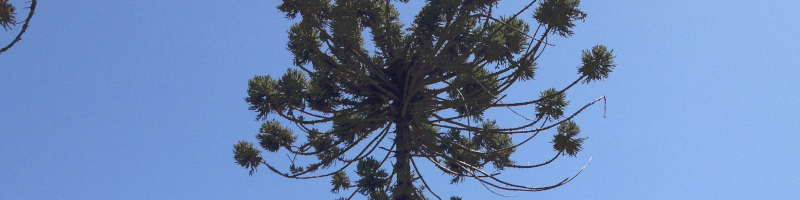

The largest group of linguistically related tribes stretches from central Chile and south to a cool green region with towering volcanoes and pristine lakes. Mapundungun, their language, was transliterated into a latin alphabet by Jesuit missionaries [6]. They are said to have migrated from Argentina through the Andes into Chile before the arrival of the Spanish. The largest of these people groups are the Mapuche [7]. Mapuche is often used colloquially to refer to all Mapundungun speakers, however there are the tehuelches, huilliche and pehuenche[8]. In Mapundugun, che means people. The pehuenche are the people of the ancient Gondwanan conifer Araucaria araucana or pehuen. The Incas fought the ancestors of the Mapuche after diplomatic missions failed [9].

Far south into the archipelagoes and the Tierra del Fuego (Land of Fire) lived many tribes which were documented by explorers. One of these tribes, the Selk’nam, are preserved in photographs demonstrating how they were exposed to the colder temperatures in little clothing and animal fur [11]. One possibility is that their extravagant skin paints also acted as a deterrent from Tabanid blood-sucking flies [12].

The origin of the name Chile is disputed [13]. Prior to the independence wars against the Spanish colonists, Chile was part of the Viceroyalty of Peru, and did not extend to the tip of the continent as it does today [14].

The central valley of Santiago [15] [16] [17] became the largest populated region in the country. The climate is near-mediterranean and features unique dry forests that are today endangered [18]. Radical changes in the landscape and climate change have caused the region to become very dry and fears continue that the Atacama may expand south.

Atacama Desert & Northern Chile

Despite being nearly biologically sterile, the Atacama Desert does harbor life in many extreme forms[22]. Volcanism of Chile’s tectonic fault is responsible for creating a chain of volcanoes beginning in the north and ending its south. Thanks to these calamitous and dangerous looking geographical conditions, water swells up from underneath because of the heat and enters into fissures of the desert where water springs begin as hot lava-heated water and flow away as cool enriching water sustaining isolated populations of grasses. Grasses play an important role in Andean communities since they are one of the main sources of fiber and thatch for roofing.

Other regions may appear to have proliferous amounts of water, but upon closer examination it is revealed that they are intensely saturated with salts that would make the area toxic to most life, except microorganisms and the flamingos the feed on them.

It isn’t until you travel to an even higher altitude where you can begin to find sparse vegetation such as bunch grasses. In this region known as the altiplano is a large landmass that is raised above the rest of the other regions and has its own unique hydrological cycle. If you are not experienced to the altitude, you may need to consult a local pharmacy for a bag of coca leaves, which when brewed into a tea, function as a light stimulant capable of remedying some of the side-effects, achieving similar results as Tylenol or other prescribed medicine.

During the few rare times it rains, because the soil is so dry and lacks porous organic material, the rain causes intense flooding as the water accumulates on the surface and moves laterally. Earthworks are constructed to manage what appear like small creeks, don’t be fooled.

The barren landscape of northern Chile creates very suitable conditions for miners to work without worrying about property disturbances like large populations and forests. This assumed reality however is not true. The large mining industry has gone into conflict with native populations who have lived in these remote areas, mostly in oases, because their operations require the finite water sources used by the locals.

An individual from northern Chile had commented once that they had never thought of plants as being native or introduced, since the climate was so harsh that he had observed that all plants used in northern Chile city landscaping were introduced.

Santiago & Central Chile

Central Chile has a near-mediterranean climate, where many crops grown in the mediterranean thrive. Prior to heavy settlement, unique dry forests existed across the various valleys. These forests are known as sclerophyllous forests [18]. One of the endemic plants of this forest system was the Chilean Palm, Jubaea chilensis. Heavy harvesting for the production of palm honey [21] and land use changes has caused it to become endangered. Today it is preserved by the city’s landscaping choices, which seeks to preserve and honor this unique species [20].

Santiago’s metropolitan region is a great place to see urban forestry in action. Urban tree selection changes across its various neighborhoods. The neighborhoods higher in elevation tend to see horticultural decisions similar to those made in the US and Europe. Ornamental trees and golf courses adorn private clubs, while the hills reveal that the climate is very different than it is in more temperate countries.

Despite that Araucaria mainly grow in the wild, few mature specimens can be found in solemn and protected areas such as the metropolitan cemetery, a small city of mausoleums and trees. There families and workers attend the mausoleums where the bones of families are stored together.

One aspect of Chile’s climate will immediately grab your attention. Because of the earth’s tilt, the rays from the Sun have to travel through more atmosphere. This process causes the seasons for each hemisphere in opposite effect [25]. When it’s summer in the northern hemisphere (June-August), it’s winter in the southern. Likewise, when it’s winter in the northern (Dec-Feb), it’s summer in the southern hemisphere. Winter in Chile is mild due to its proximity to the ocean, however the mountains receive snow and in the valleys rain precipitates at low temperatures causing dreadfully cold days. Most homes do not have central heating, so a sweater and jacket become often worn inside and outside. Evergreen trees stay … green. However, the valleys are often composed mostly of deciduous trees. Air quality in these valleys improves in winter, but in summer they are often polluted with smog. This has been an issue that many are trying to resolve, and urban forestry is one solution. Other solutions have been dedicating large boulevards to bike-only days during one day of the week.

Santiago is one of many cities in central Chile. Many destinations are on the coast where old ports continue to work today. It’s on the way to the coast from Chile, where travellers will encounter a secondary coastal mountain range, classified as hills by locals. In this coastal mountain range there are many forests and protected areas that are greatly different than the busy cities of the coast and the metropolitan region. Recently these areas have been victim to uncontrollable forest fires due to invasive Australian Eucalyptus that reaches lower into the water table than native trees, and is highly combustible [24].

Los Lagos & Southern Chile

The cover image of this article shows the Los Lagos region or Lake District of southern Chile. Notice the similarity between that photo, and the images of Madison, WI’s lakes in ‘Catfish Valley’. Similar to Wisconsin, southern Chile experienced glaciation, however the direction of the glaciers flowed west to east into the ocean, unlike in North America, where they flowed north to south into the continent. These conditions created large lakes in the steep valleys between volcanos. These volcanic lakes are so steep that they have currents that go into their interior. Swimmers have been warned to avoid swimming near the middle, since there have been cases of people falling and being swept under. Unlike the lakes of Madison, and other parts of the midwest, these lakes lack large quantities of flora, and have thankfully not been contaminated by invasive flora, as Madison and other metropolitan lakes in the United States have.

This region was one of the last additions to the republic of Chile after it became independent from Spain. Politicians, such as Vicente Perez Rosales, worked together with officials in central Europe to bring skilled migrants to southern Chile to help the government colonize the lands. Many were told that they would farm this once forested mountainous region. This had the negative consequence of increasing deforestation and causing wildfires to utilize poor agricultural soils. In addition, landscaping plants from central Europe have become invasive.

South of the city of Puerto Montt, the coastline turns into a thousands of miles of fjords and islands. The coastal land is often windswept, where as the interior has forests. The first and largest island Chiloé Island is known for its folklore of witches, warlocks and black magic.

(Mammo et al, 2017)[8a]

Cohuín, Chiloe Island, Chile. 2022.

Chiloe Island, Chile. Dec 2023.

Autor: Gustavo Meneses

Published: 2023-01-28

Revisado: 2023-12-22

Plants

[P1] Delgado-Paredes, GE. Vásquez-Díaz, C. Esquerre-Ibañez, B. Huamán-Mera, A. Rojas, C. “Germplasm collection, in vitro clonal propagation, seed viability and vulnerability of ancient Peruvian cotton (Gossypium barbadense L.). Pakistan Journal of Botany, Vol 53, Issue 4, pp. 1259-1270. Mar 2021. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/350592596_GERMPLASM_COLLECTION_IN_VITRO_CLONAL_PROPAGATION_SEED_VIABILITY_AND_VULNERABILITY_OF_ANCIENT_PERUVIAN_COTTON_GOSSYPIUM_BARBADENSE_L

[P1-2] “Gossypium barbadense L.” Plants of the World Online. Kew. Website. Accessed Jan 29, 2023. https://powo.science.kew.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:559677-1

[P2] “Cynara cardunculus L.” Plants of the World Online. Kew. Website. Accessed Jan 29, 2023. https://powo.science.kew.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:200876-1

[P2-2] “Cynara in Flora of Chile”. Flora of Chile. eFloras. Website. Accessed Jan 29, 2023. http://www.efloras.org/florataxon.aspx?flora_id=60&taxon_id=108971

[P3] “Citrus × limon“. Plants of the World Online. Kew. Website. Accessed Jan 29, 2023. https://powo.science.kew.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:60454758-2

[P4] Gay, Claudio. “Historia fisica y politica de Chile: Agricultura: tomo segundo.” Museo de Histoira Natural de Santiago, 1865, pg.92. memoriachilena, Biblioteca Nacional de Chile. PDF. Accessed Jan 29, 2023. http://www.memoriachilena.gob.cl/602/w3-article-7879.html

[P4-2] “Zea mays“. Plants of the World Online. Kew. Website. Accessed Jan 29, 2023. https://powo.science.kew.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:426810-1

[P5] “Jubaea chilensis“. Plants of the World Online. Kew. Website. Accessed Jan 30, 2023. https://powo.science.kew.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:131713-2

[P5-2] Castro San Carlos, Amalia. “Historia y evolución de la miel de palma chilena: de producto típico a industrial (1550-1941).” Universidad Mayor. http://www.asociacionhistoriasocial.org.es/download/IX_Congreso/4_Sesion/4.02_Castro_Amalia_Historia_de_la_miel.pdf

[P5-3] “Manual de Capacitación del Pequeño Propietario.” Ministerio de Agricultura. CONAF. PDF. Accessed Jan 30, 2023. https://investigacion.conaf.cl/archivos/repositorio_documento/2018/10/Manual-Proyecto-003-2012.pdf

[P5-4] Salinas, M. Eugenia. “Detectan mercado ilegal de cocos de palma chilena.” Litoralpress. Apr 15, 2022. Website. Accessed Jan 30, 2023. https://www.litoralpress.cl/sitio/Prensa_Texto?LPKey=7HM7EPEE3BX3MVWJJ6PRMHJAX674KC6OSRLDLSRAKDNRKCMIWLZA

References

[1] Moreira-Muñoz, A. “The Austral floristic realm revisited.” Journal of Biogeography. Aug 8, 2007. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2007.01757.x

[3] Barnhart, Edwin. “Episode 18: Cuzco and the Tawantinsuyu Empire, Lost Worlds of South America.” The Great Courses. Amazon Prime. 2012. https://www.amazon.com/gp/video/detail/B00QHER5S8/ref=atv_dp_share_cu_r

[4] “The Great Inka Road: Engineering an Empire” Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian, Jun 2020. Website. Accessed Jan 29, 2023. https://americanindian.si.edu/inkaroad/index.html

[5] Pighi Bel, Pierina. “El desaparecido asentamiento inca sobre el que se fundó Santiago de Chile.” BBC News Mundo. March 13, 2021. Website. Accessed Jan 27, 2023. https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias-56258737

[6] [Bernhard Havestadt], Chilidúgu Sive Tractatus Linguae Chilensis Opera Bernardi Havestadt. Editionem Novam Immutatam Curavit Dr. Julius Platzmann, Teubner, Lipsiae, 1883 [2 Vols.]

https://archive.org/details/HavestadtChiliduguPlatzmann1883

[7] Meyer Rusca, Walterio. 1952. “Voces indigenas del Lenguaje popular sureño: 550 chilenismos.” San Francisco Padre Las Casas. pg. 11, 65. https://www.bcn.cl/catalogo/detalle_libro?bib=225850

[8] “Mapuche-English Dictionary.” InterPatagonia. Website. Accessed Jan 27, 2023. https://www.interpatagonia.com/mapuche/dictionary.html

[9] Soublette, Gaston. “Entrevista a Gastón Soublette – Parte III: La Cultura Mapuche.” Universitas Nueva Civilización, Youtube, Oct 3, 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N27LAd906yM

[10] “Amount of DNA (c-value) and Number of Chromosomes (n-value).” Open Genetics. Thompson Rivers University. Website. Accessed Jan 27, 2023. https://opengenetics.pressbooks.tru.ca/chapter/metaphase-chromosome-spreads/

[11] “Category: Fur clothing of Selk’nam people”. Wikimedia Commons. Accessed Jan 27, 2023. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Fur_clothing_of_Selk%27nam_people

- Notice how people groups who live in temperate or extreme cold environments are highly dependent on animals, whereas people groups in milder climates develop plant based fabrics. Agroforestry practices are inclusive by allowing people to develop gardens for animals.

[12] Horváth, G. Pereszlényi, A. Åkesson, S. Kriska, G. 2019. “Striped bodypainting protects against horseflies.” The Royal Society Publishing. https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rsos.181325

[13] “Etimología de CHILE.” deChile. Website. Accessed Jan 27, 2023. http://etimologias.dechile.net/?chile

[14] Chile a través de su cartografía (1766 – 1929). ArcGIS Application, Servicio Nacional del Patrimonio Cultural. Website. Accessed Jan 29, 2023. https://geoportal.patrimoniocultural.gob.cl/cartografia_historica_de_chile/

[15] “Camino de Santiago: What’s in a name?” Duperier’s Authentic Journeys, Jan 16, 2017. Blog. Accessed Jan 29, 2023. https://www.authentic-journeys.com/blog/whats-in-a-name/

[16] Nutter, Nick. “History of the Order of Santiago in Andalucia.” visit andalucia, Sep 16, 2022. Website. Accessed Jan 29, 2023. https://www.visit-andalucia.com/order-of-santiago-andalucia/

[17] “Surveying Political Force.” Vistas: Spanish American Visual Culture, 1520-1820. Smith College. Website. Accessed Jan 29, 2023. https://www.smith.edu/vistas/vistas_web/units/surv_politics.htm

[18] Amigo, J. Flores-Toro, L. 2013. “Sclerophyllous forests and preforests of Central Chile: Lithraeion causticae alliance.” International Journal of Geobotanical Research, Vol 3, pp. 47-67.https://www.researchgate.net/publication/260827942_Sclerophyllous_forests_and_preforests_of_Central_Chile_Lithraeion_causticae_alliance

[19] “Los ferrocarriles en la Región de Atacama, Chile.” geovirtual2. Website. Accessed Jan 30, 2023. http://www.geovirtual2.cl/Museovirtual/FFCC/Atacama-Ferrocarril-Entrada-00.htm

[20] Fuentes, F. “Parte reposición de palmas en Plaza de Armas.” Plataforma Urbana. El Mercurio. Aug 4, 2014. Website. Accessed Jan 30, 2023. https://www.plataformaurbana.cl/archive/2014/08/04/parte-reposicion-de-palmas-en-plaza-de-armas/

[21]”Guarapo.” Gobierno de Canarias. PDF. Accessed Jan 30, 2023. https://marcacanaria.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/miel-de-palma-marca-canaria.pdf

[22] “Chile (North)” playlist. Crime Pays But Botany Doesn’t. Youtube. Accessed Jan 30, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A6ShaNK7s7A&list=PLK8bda0Bqux1qKZYbTn6VbdSbX7E1MXfI

[23] Hamilton, Jim. “Silvopasture: Establishment & management principles for pine forests in the Southeastern United States.” USDA National Agroforestry Center, Feb 2008. PDF. Accessed Jan 30, 2023. https://www.fs.usda.gov/nac/assets/documents/morepublications/silvopasturehandbook.pdf

[24] Rodríguez-Suárez, JA. Soto, B. Perez, Diaz-Fierros, F. “Influence of Eucalyptus globulus plantation growth on waer table levels and low flows in small catchment.” Journal of Hydrology, vol 396, issues 3-4, 2011. pp. 321-326. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022169410007237

[25] Dixon, Michael. Strenth, Ned. Chodacki, Griffin. LeBrasseur, Kaitlynn. Maddox, Timothy. “9 – Climate & Biomes” Biology 1409 – Man and the Environment Lab. Angelo State University. https://www.angelo.edu/faculty/mdixon/ManEnvironment/climate2.htm

Images

[1a] Clamosa, Fama. “File:Gondwana 420 Ma.png”. GPlates. March 3, 2018. Wikimedia Commons. Accessed Jan 27, 2023. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gondwana_420_Ma.png

[2a] Jones, Adam. “File:Inca Stone Architecture – Sacsayhuaman – Peru 02 (3786204472).jpg”. Apr 26, 2005. Wikimedia Commons. Accessed Jan 27, 2023. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Inca_Stone_Architecture_-Sacsayhuaman–Peru_02(3786204472).jpg

[3a] “File:Peru, Inca Period, 15th-16th Century – Inka Khipu (Fiber Recording Device) – 1940.469 – Cleveland Museum of Art.tif” Circa 1400-1532. Cleveland Museum of Art. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Peru,Inca_Period,_15th-16th_Century–Inka_Khipu(Fiber_Recording_Device)-_1940.469-_Cleveland_Museum_of_Art.tif

[4a] Elias, Claudio. “File:Museo LP 001.JPG”. May 2009, Wikimedia Commons. Accessed Jan 27, 2023. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Museo_LP_001.JPG

[5a] Zonneveld, BJM. 2012. “Figure 1.”, “Genome sizes of all 19 Araucaria species are correlated with their geographical distribution.” Plant Systematics and Evolution, vol 298, pp.1249-1255. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00606-012-0631-7#Fig1

[6a] lautaroj ,”File:Araucaria araucana – Parque Nacional Conguillío por lautaroj – 001.jpg”., Dec 31, 2010. Wikimedia Commons, Accessed Jan 27, 2023. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Araucaria_araucana_-Parque_Nacional_Conguillío_por_lautaroj-_001.jpg

[7a] Hall, Bob. “File:Araucaria heterophylla Endeavour Lodge Norfolk Island 3.jpg”. Nov 6, 2011. Wikimedia Commons. Accessed Jan 27, 2023. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Araucaria_heterophylla_Endeavour_Lodge_Norfolk_Island_3.jpg

[8a] Mammo, Fitsum. Mohanlall, Viresh. Shode, Francis. “Gunnera perpensa L.: A multi-use ethnomedicinal plant species in South Africa”. Jan 2017. African Journal of Science Technology Innovation and Development. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/20421338.2016.1269458